Karen Costello is a 'Country Lawyer', Associate Tribal Court Judge and City Attorney Music-Made Lawyer

"I think if people tell you they walk a straight path to their journey-they're not noticing all the little detours they've taken."

So says Karen Costello of Costello Law Office in Coos Bay, while tracing the spiderweb of paths she took on her way to becoming a lawyer, and then the unexpected route she followed as a non-native authority on Indian and tribal law, whose expertise brought her national recognition.

It was not until she was 35, having already earned her bachelor's and master's

degrees in music and a career as a university lecturer and composer, that she entered law school. She was no longer able to resist the lure of the law, something she had felt since a teenager observing the involvement of her parents and their friends in the farm labor movement in North Dakota.

"It was the '70s," she recalls of her first real awareness of the law profession. "It was knowing that lawyers were working for social justice. I didn't know how or why, but just knew stories of lawyers who'd helped people. But," she adds, "I never saw myself as a person who could do that."

Self-Doubt Turns to Belief

Costello remembers being dissuaded from her interest by a guidance counselor at her West Fargo, North Dakota, high school, who told her, "That's really hard for girls. That would be really rigorous. Hard to have a family and do that."

Still, she was oddly drawn to law librar-les. Even after giving up her music studies to support her husband's academic and professional path, she browsed through law libraries wherever they lived, in Mon-tana, New Mexico and ultimately back in North Dakota.

One day while pushing her baby daughter's stroller through the library stacks at the University of North Dakota School of Law, she was approached by a woman law professor who asked, "Are you a IL?" Costello recalls, "And I said, 'Oh, no. Not me.' She looked at me and said. "Well. come and see me sometime.' Ten vears later, I went to see her.

In the interim, Costello got divorced, completed both her bachelor's and master's degrees in music, and was a lecturer in music theory and composition at University of North Dakota while composing commissioned chamber music for two to five play-ers. Looking back, Costello now views her university music studies as the foundation upon which she could actually imagine herself embarking on a career in law.

"It really took finishing my music degree and my master's degree in music to give me the ability to see in myself that I could do that," she says. "My music degrees were special for what they gave to me in that field, but they were really special to me in that they allowed me to understand and feel my own worth. I think that's thei most important thing in my life: those mu sic degrees gave me access to myself and mi power as a human being."

Interest in Indian Law

University of North Dakota, in Grand Forks, where Costello studied music, is home to the state's only law school. It is in turn one of only a handful of law schools in the U.S. that offer a certificate in Indian law.

Also, it's home to the Northern Plains Indian Law Center.

Although the certificate program was not yet in effect during Costello's law school years there, she did avail herself of several classes on federal Indian law and tribal law, and participated in the Tribal Justice Institute and the law school's Legal Aid Clinic's Tribal Law Program. It was for a purely practical reason, she says.

"I was an older-than-average law stu dent and I thought that when I hit the job market I should have something special on my resume so that I could overcome that. says Costello. Through the Tribal Law Pro-gram, she seized an opportunity to serve as one of several juvenile prosecutors at the Spirit Lake Lakota Reservation.

"My intent was to get experience, but what happened is that I fell in love with it, she savs. "It was intellectually rigorous and compelling, but it was so personally inter esting and needed. I mean, you can't go out on a reservation in North Dakota and not see that there's a need."

Costello says her love of the job grew in relation to the tribe's appreciation of her work. "I didn't alwavs feel a sense of wel coming in other legal circles. Not everybody was wanting to welcome a 38-year-old female new lawver in North

bakor and not see that there's a need."

Costello says her love of the job grew in relation to the tribe's appreciation of her work. "I didn't alwavs feel a sense of wel coming in other legal circles. Not everybody was wanting to welcome a 38-year-old female new lawver in North Dakota," she says. "But the tribe was welcoming. I wasn't turned away, I was welcomed, and so ther my dedication grew and grew and grew.

Her first job out of law school was at Wisconsin Judicare Legal Aid, through which she worked with the state's 11 tribes, also advising and representing tribes na tionally in matters of legal policy and development of court systems. She looked after younger tribal members, particularly those who were disabled, for whom she helped set up trusts to manage their shares from casino revenues.

She remembers in particular one thorny case for which she had to place five young siblings who shared the same mother but had different fathers. 'The case involved two states and three tribes. "I remember getting that assignment and thinking, 'I don't know what to do,' Costello recalls. "But I think having a background in the he arts was helpful."

How so?

Practicing law, she says, "is very much like being a performing musician. You spend hours and hours and hours in the practice room and then you execute maybe 20 minutes of performance."

Musicians, she explains, need to have a thorough technical grasp of their material (playing the instrument, reading the mu-sic) in order to create musical expression. "I think the law can be like that," she says. "We don't learn every law in law school; we learn how to learn the law, which is sometimes a very technical undertaking. Then we have to apply it to a very real-world situation."

In the end, the case was successful and Costello credits her unusual approach of ex amining the situation as if she were encountering a new piece of music. "It was like,"'What do I have here? How can I approach this?' And then I just started pulling back the layers and learning it. It was a successful case and a memorable case tor me. And now those children are all grown."

Love and Law in Oregon

It was Costello's expertise in tribal lan that indirectly brought her to Oregon. She puts it more succinctly: "I came to Oregon and the reason was love.

She met Donald O. Costello, her husband since 2006, while teaching a seminar for tribal court judges at The National Judicial College at the University of Nevada in Reno. Her husband-to-be was then chief judge of the Coquille Indian Tribe and the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians.

"He's kind of a well-known guy in the field so I knew who he was before I met him," she says. "I was a little intimidated about teaching a class he'd be in because I thought he probably should teach the class instead of me."

He asked her out to dinner and two years later they were married. Once her daughter, Sunniva, graduated from high school in Wisconsin, the family of three moved to Coos Bay, where in 2014 the couple opened their own firm, Costello Law Office. Drew Scott Betts joined the firm as an associate lawyer in November 2022.

Don Costello has since retired from in dicial work, but Karen Costello serves as the associate judge for the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indi-ans. She is also the Coquille city attorney.

"We are a general civil practice firm," she says, adding, "We're country lawyers so we do a lot of things."

And as a country lawyer, of course, she has the freedom to hang a "Gone Hiking" sign on her door (if she has one) and disappear into the woods or along a meandering coastal trail. "We're a full-service, full-time law firm, but if it's a real sunny day you might find me and my associate taking a hike rather than sitting at a desk," she explains.

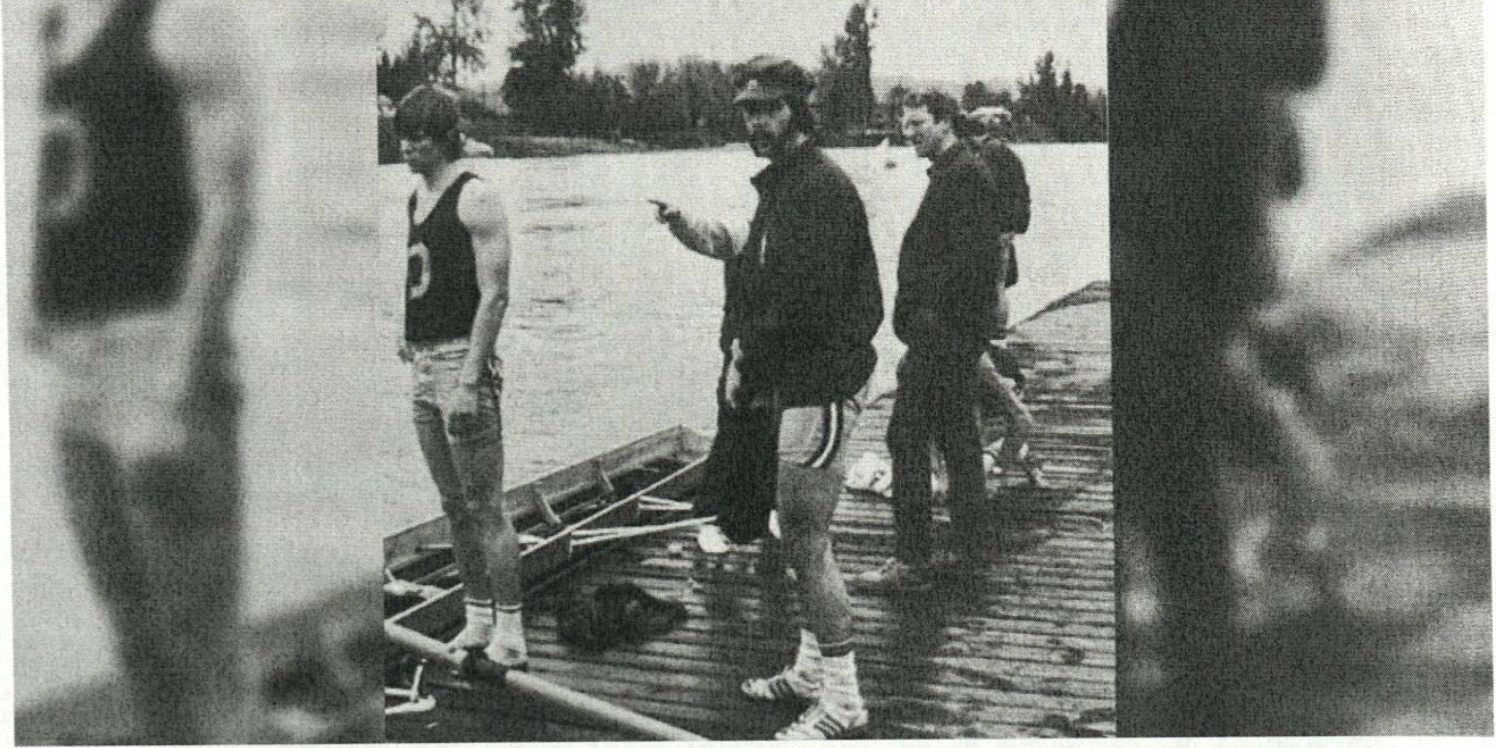

Don Costello, on the other hand, is likely to be found on Tenmile Lake, rowing a sculling boat, a sport he's enjoyed since his college days in the '60s.

Her Music Endures

But don't think for a minute that Karen Costello has given up music. After all, music has been a major part of her life since her parents surprised her and her older sis-ter, Dana, with a piano of their own. Their childhood play revolved around that piano and their playing and singing led ultimately to university music scholarships, making them the first members of their family to attend college.

These days, however, Costello's musical side is expressed in a simpler fashion than composing chamber music for ensembles. She plays her own made-in-Oregon Irish harp, built in Corvallis by master harp maker David Thormalen. Her audience has shrunk since the days when her works were recorded and performed in concert halls.

But Costello couldn't be happier playing to one dog and two cats, who show their appreciation by promptly falling asleep. Her husband is the one member of the cozy audience who applauds. But he is, she says,"the biggest fan of anything I do."

Enjoying the southern Oregon coastal lifestyle and her work for the tribes and the Coos County community, Costello is

content with her life. Her parents and sister, having relocated from North Dakota, live nearby, as does her daughter, Sunniva Jel-sing, and granddaughter, Vivienne Jelsing She has no regrets about minimizing her life in music in order to embrace the law.

As she saw the situation, at the point when she was ready to stray from her path

and shift from music to the law• "I wanted to do something that involved others more and was less focused on me and my own thoughts and creativity, something that focused more on people and humanity.'

Susan Hauser, a native Oregonian, now lives and does freelance writing from Indiana, where she is closer to her children and grand-children. She wrote the April 2023 profile of Cadence Whiteley and the June 2022 feature piece about the Oregon State Bar Leadership Institute.